Sunday, October 31, 2004

Ten Questions

So, bin Laden supposedly admits to 9/11:

http://www.truthout.org/docs_04/103004A.shtml

I guess people are starting to ask too many questions about the events of that day - what better way to throw folks off the scent than a 'confession from the accused'.

Okay, here's a few questions I'd like 'criminal mastermind' bin Laden to answer:

Did he inform the CIA of his plans since pre-9/11 insider trading on UA and AA options lead to the highest ranks of the CIA?

http://www.whatreallyhappened.com/illegaltrades.html

Did he ask FEMA to be in New York on 9/11?

http://www.whatreallyhappened.com/fematape.html

Did he tell Larry Silverstein to prepare WTC 7 for demolition on 9/11?

http://whatreallyhappened.com/cutter.html

Did he inform the Israelis of his plans?

http://www.whatreallyhappened.com/fiveisraelis.html

Did he stand down the USAF?

http://whatreallyhappened.com/911stand.html

Did he phone New York's authorities to inform them that the WTC was going to collapse?

http://www.whatreallyhappened.com/wtc_giuliani.html

Did he plant explosives in the twin towers to ensure perfect collapses?

http://www.whatreallyhappened.com/911_smoking_gun.html

Did he make provisions to ensure the investigation into the collapse of the twin towers was an underfunded farce

http://www.whatreallyhappened.com/wtc_fema_911.html

Did he instruct President Bush to try and limit the scope of the 9/11 probe?

http://www.cnn.com/2002/ALLPOLITICS/01/29/inv.terror.probe/

Why didn't he know the identities of his 'hand-picked' hijackers?

http://whatreallyhappened.com/hijackers.html

Answers on a postcard please.

From: What Really Happened?

ß

Ten Questions

Growing Up in Trengganu #43275

Our cousin Dah was one day knocked sideways by a Tok Peraih travelling at speed from Kedai Payang to a place in Ladang.

Kedai Payang — if you know Trengganu — is almost in the town centre, and Ladang some fifteen minutes away, maybe faster, seeing as how the Tok Peraih flew. Tok Peraihs were sinewy men often found under a conical terendak hat, and they rode sturdy bikes with a rack in the back on which was placed a rectangular cane basket filled with the latest fruits of the sea. We'd all skated or slipped in the fishmarkets of Kuala Trengganu, but cousin Dah was the only family member I knew who'd had the fish market come crashing on her.

sturdy bikes with a rack in the back on which was placed a rectangular cane basket filled with the latest fruits of the sea. We'd all skated or slipped in the fishmarkets of Kuala Trengganu, but cousin Dah was the only family member I knew who'd had the fish market come crashing on her.

The peraihs were middlemen who waited all day in the coffee shops then sprang to life in late afternoon when the payang boats came back to shore. They were tough cookies and hard bargainers, and wore baggy khaki shorts with draped over batik sarongs, rolled up to the knee, with the seams pulled up and tucked into the wiastband. On cooler days they'd discard the terendak and wrap their heads in a band of long material quite in the way of the Kelantanese semutar. By five o'clock, at peraih speed, the fish would be in the Ladang market opposite my old Malay school — the kembong, and selar kuning, and ikan keras ekor, ikan jebong and the occasional ttuke, probably cousin to the skate or pari — the sea smell wafting to the roundabout later made famous by the Trengganu turtle.

As it happened, cousin Dah was crossing the road when the Tok Peraih came at breakneck speed on his way to an important customer. She fell to the road in shock, but was otherwise unhurt, and her pride smelt of fish that day. The Tok Peraih merely shook his head in disbelief and continued on his urgent journey, while his one free hand pressed even more agitatedly on the rubber bulb of his handle-bar horn that went phat-phat! all the way.

Late afternoon was peraih time in the streets of coastal Kuala Trengganu, when these fish couriers pedalled fast and furious to their customer-retailers in Ladang, Pasir Panjang or Chabang Tiga, that bustling market at the intersection of roads that took us to deeper parts of Trengganu.

This occasion of cousin Dah and the middleman was one that I savoured with much hilarity — only after discovering that she was physically unscathed, of course — because the peraihs were busy and sturdy men who were only visible at speed, and there wasn't one that I knew. You only saw them dismounted among the market stallholders, and that was after their business was done, as they walked about with their sarong skirts lifted like stage curtains half-drawn when the show was nearly over. And then they'd disperse and disappear till the butt end of the following business day, with their bicycle horns going phat-phat! phat-phat! warning people like Dah of their pace of travel.

I remember Ladang not only because Dah came to grief with a basket of fish near there on that fateful day. At peraih speed, it was a good few minutes still from Ladang that she met the flying wheel: a place near the bend known to us as Tanjong Mengabang, in a landscape of coastal shacks and smart houses, and coconut trees all the way to the sea. Tanjong Mengabang had a peculiar hum about it, and a funny breeze that blew in a certain chill.

a place near the bend known to us as Tanjong Mengabang, in a landscape of coastal shacks and smart houses, and coconut trees all the way to the sea. Tanjong Mengabang had a peculiar hum about it, and a funny breeze that blew in a certain chill.

When Mother told me stories of Trengganu past, she often spoke of Pak Mat Mengamok, who one day went berserk after some matrimonial crisis and went on a killing spree. Pak Mat was buried there she said, among the coconut trees of Tanjung Mengabang, and funnily enough, it was near the house of another Pak Mat, a telecoms linesman in his daytime job, who was often at our house during weekends for some bits of carpentry. My father was a telephone operator at the Kuala Trengganu exchange in those days, and Pak Mat was the man who put those copper lines on poles that went for as long as you could see; so they shared a certain camaraderie.

It was near Pak Mat's house that cousin Dah had her piscatorial day, but it wasn't something that he remembered clearly. Just over three years ago, when I saw my father for the last time, we were chatting in the front of the house in Kuala Lumpur when a car drove into the driveway and out from the passenger side came a rheumy eyed man so full of smile. This was Pak Mat of years ago, who used to perch on poles among the copper wires, but now he was walking very slowly.

They had a lot to talk about as they'd not seen each other for many years. Then Pak Mat asked about a certain person, my father's friend, who used to be his boss at the Telephone Exchange in Kuala Trengganu. He'd come to Kuala Lumpur with a purpose, he said, because many years ago, the boss gave him 15 ringgit too much in his pay packet, and now he wanted to hand it back before he returned to his Maker.

Like our cousin Dah I had Tanjong Mengabang and the Tok Peraihs come hurtling back to me that day; but most of all, I was close to tears by Pak Mat's honesty.

ß

Growing Up in Trengganu #43275

Kedai Payang — if you know Trengganu — is almost in the town centre, and Ladang some fifteen minutes away, maybe faster, seeing as how the Tok Peraih flew. Tok Peraihs were sinewy men often found under a conical terendak hat, and they rode

sturdy bikes with a rack in the back on which was placed a rectangular cane basket filled with the latest fruits of the sea. We'd all skated or slipped in the fishmarkets of Kuala Trengganu, but cousin Dah was the only family member I knew who'd had the fish market come crashing on her.

sturdy bikes with a rack in the back on which was placed a rectangular cane basket filled with the latest fruits of the sea. We'd all skated or slipped in the fishmarkets of Kuala Trengganu, but cousin Dah was the only family member I knew who'd had the fish market come crashing on her.

The peraihs were middlemen who waited all day in the coffee shops then sprang to life in late afternoon when the payang boats came back to shore. They were tough cookies and hard bargainers, and wore baggy khaki shorts with draped over batik sarongs, rolled up to the knee, with the seams pulled up and tucked into the wiastband. On cooler days they'd discard the terendak and wrap their heads in a band of long material quite in the way of the Kelantanese semutar. By five o'clock, at peraih speed, the fish would be in the Ladang market opposite my old Malay school — the kembong, and selar kuning, and ikan keras ekor, ikan jebong and the occasional ttuke, probably cousin to the skate or pari — the sea smell wafting to the roundabout later made famous by the Trengganu turtle.

As it happened, cousin Dah was crossing the road when the Tok Peraih came at breakneck speed on his way to an important customer. She fell to the road in shock, but was otherwise unhurt, and her pride smelt of fish that day. The Tok Peraih merely shook his head in disbelief and continued on his urgent journey, while his one free hand pressed even more agitatedly on the rubber bulb of his handle-bar horn that went phat-phat! all the way.

Late afternoon was peraih time in the streets of coastal Kuala Trengganu, when these fish couriers pedalled fast and furious to their customer-retailers in Ladang, Pasir Panjang or Chabang Tiga, that bustling market at the intersection of roads that took us to deeper parts of Trengganu.

This occasion of cousin Dah and the middleman was one that I savoured with much hilarity — only after discovering that she was physically unscathed, of course — because the peraihs were busy and sturdy men who were only visible at speed, and there wasn't one that I knew. You only saw them dismounted among the market stallholders, and that was after their business was done, as they walked about with their sarong skirts lifted like stage curtains half-drawn when the show was nearly over. And then they'd disperse and disappear till the butt end of the following business day, with their bicycle horns going phat-phat! phat-phat! warning people like Dah of their pace of travel.

I remember Ladang not only because Dah came to grief with a basket of fish near there on that fateful day. At peraih speed, it was a good few minutes still from Ladang that she met the flying wheel:

a place near the bend known to us as Tanjong Mengabang, in a landscape of coastal shacks and smart houses, and coconut trees all the way to the sea. Tanjong Mengabang had a peculiar hum about it, and a funny breeze that blew in a certain chill.

a place near the bend known to us as Tanjong Mengabang, in a landscape of coastal shacks and smart houses, and coconut trees all the way to the sea. Tanjong Mengabang had a peculiar hum about it, and a funny breeze that blew in a certain chill.

When Mother told me stories of Trengganu past, she often spoke of Pak Mat Mengamok, who one day went berserk after some matrimonial crisis and went on a killing spree. Pak Mat was buried there she said, among the coconut trees of Tanjung Mengabang, and funnily enough, it was near the house of another Pak Mat, a telecoms linesman in his daytime job, who was often at our house during weekends for some bits of carpentry. My father was a telephone operator at the Kuala Trengganu exchange in those days, and Pak Mat was the man who put those copper lines on poles that went for as long as you could see; so they shared a certain camaraderie.

It was near Pak Mat's house that cousin Dah had her piscatorial day, but it wasn't something that he remembered clearly. Just over three years ago, when I saw my father for the last time, we were chatting in the front of the house in Kuala Lumpur when a car drove into the driveway and out from the passenger side came a rheumy eyed man so full of smile. This was Pak Mat of years ago, who used to perch on poles among the copper wires, but now he was walking very slowly.

They had a lot to talk about as they'd not seen each other for many years. Then Pak Mat asked about a certain person, my father's friend, who used to be his boss at the Telephone Exchange in Kuala Trengganu. He'd come to Kuala Lumpur with a purpose, he said, because many years ago, the boss gave him 15 ringgit too much in his pay packet, and now he wanted to hand it back before he returned to his Maker.

Like our cousin Dah I had Tanjong Mengabang and the Tok Peraihs come hurtling back to me that day; but most of all, I was close to tears by Pak Mat's honesty.

ß

Growing Up in Trengganu #43275

Saturday, October 30, 2004

Swimming With No Hands

On Monday 25th October, the eleventh day of Ramadhan, an army truck pulled away from a demonstration with a human load, arms tied behind their backs and stacked face down, four deep, like logs. There were other trucks too with similar cargo: according to the BBC, 1300 demonstrators were arrested and similarly packed.

Seventy-eight people did not end the journey. to the military headquarters alive: they suffocated in the human pile, and their bodies were returned to their families as an iftar surprise.

to the military headquarters alive: they suffocated in the human pile, and their bodies were returned to their families as an iftar surprise.

You may not have heard of this place; but then again, you may have been to the country to enjoy its tourist resorts and alluring fleshpots. This was Tak Bai, Southern Thailand, last Monday, and the human cargo, tied and stacked, were Muslim demonstrators.

This wasn't the first time this had happened in paradise. On 28 April this year, more than a hundred Muslims died in clashes with the police. They, the Muslims, were armed with knives and machetes as the police mowed them down with bullets.

There're problems in Southern Thailand that have been simmering for a long time, it's basically about Patani but four other provinces — Yala, Narathiwat, Satun and Songkhla — are also involved. More than 5 million Thai Muslims live in those parts. These are Malay-Muslims living in a predominantly Buddhist nation, and they complain of discrimination, cultural subjugation and annihilation. Many Malay place names in Thailand have been changed by the authorities into Thai place names to snuff the idea out from southern Muslims with nationalist aspirations.

Already the name calling has started.

After the attacks in April, Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra said they were local bandits; army chief General Chaiyasidh Shinawatra said many of them were under the influence of drugs; General Pallop Pinmanee, the man who ordered many of them shot in the local Mosque said they were Muslim separatists trained abroad. The Nation newspaper pronounced a new danger for Thailand from a 'fanatical ideology' now appearing on a grand scale.

It is not unusual for people in a land dominated by people they see as a 'colonising' power to fight for self-determination. It's a right enshrined in the Universal Declaration, and no amount of name-calling will take that away from them. But once name-calling sets in, and in the present climate of the world, it's difficult to see how they can be heard.

Meantime, according to General Pinmanee, "the military phase has just started."

The Tak Bai tragedy last Monday took many lives. According to a Southern Thai source, at least 120 demonstrators died, with 730 still missing. Those who were asphyxiated in the army trucks weren't the only ones who met terrible deaths. Thirty-five demonstrators were dumped into a river with their hands tied on the same day.

ß

Swimming With No Hands

Seventy-eight people did not end the journey.

to the military headquarters alive: they suffocated in the human pile, and their bodies were returned to their families as an iftar surprise.

to the military headquarters alive: they suffocated in the human pile, and their bodies were returned to their families as an iftar surprise.

You may not have heard of this place; but then again, you may have been to the country to enjoy its tourist resorts and alluring fleshpots. This was Tak Bai, Southern Thailand, last Monday, and the human cargo, tied and stacked, were Muslim demonstrators.

This wasn't the first time this had happened in paradise. On 28 April this year, more than a hundred Muslims died in clashes with the police. They, the Muslims, were armed with knives and machetes as the police mowed them down with bullets.

There're problems in Southern Thailand that have been simmering for a long time, it's basically about Patani but four other provinces — Yala, Narathiwat, Satun and Songkhla — are also involved. More than 5 million Thai Muslims live in those parts. These are Malay-Muslims living in a predominantly Buddhist nation, and they complain of discrimination, cultural subjugation and annihilation. Many Malay place names in Thailand have been changed by the authorities into Thai place names to snuff the idea out from southern Muslims with nationalist aspirations.

Already the name calling has started.

After the attacks in April, Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra said they were local bandits; army chief General Chaiyasidh Shinawatra said many of them were under the influence of drugs; General Pallop Pinmanee, the man who ordered many of them shot in the local Mosque said they were Muslim separatists trained abroad. The Nation newspaper pronounced a new danger for Thailand from a 'fanatical ideology' now appearing on a grand scale.

It is not unusual for people in a land dominated by people they see as a 'colonising' power to fight for self-determination. It's a right enshrined in the Universal Declaration, and no amount of name-calling will take that away from them. But once name-calling sets in, and in the present climate of the world, it's difficult to see how they can be heard.

Meantime, according to General Pinmanee, "the military phase has just started."

The Tak Bai tragedy last Monday took many lives. According to a Southern Thai source, at least 120 demonstrators died, with 730 still missing. Those who were asphyxiated in the army trucks weren't the only ones who met terrible deaths. Thirty-five demonstrators were dumped into a river with their hands tied on the same day.

ß

Swimming With No Hands

Friday, October 29, 2004

Growing Up In Trengganu #50976

To move onward to Besut after the bustle of Kuala Trengganu the bus had to go down the slope and struggle up the ramp onto the ferry at Bukit Datu. It was a hairy experience, but too late to turn back now, there were scores of other vehicles big and small in the tailback, waiting to pour into the dip for a ride across the swell.

The ferry was a raft built of blocks of wood that took the weight of four or six vehicles, assorted pedestrians and people cycling into the green yonder. It was pulled by a tug across the Trengganu river in one of its most meancing phases, to the bank across, from where our journey would continue. Ferries crossed many rivers in Trengganu then, in Dungun there was a ferry point, and in Kemaman there was one at a place called Geliga. An express bus once slipped its brakes on the deep incline to the ferry over there and dove into the river. I remember that early evening in Kuala Trengganu when our poor cousin from Seberang Takir came back quite dead and sodden with many other unfortunate souls, all laid out in the back of a lorry.

The road to Besut was heat and dust over a long stretch that wound and dipped through dense jungle. In the monsoon months, seen through the condensation in the window, the view became smudgy watercolour, smearings of green against the brooding sky, and the continual swish-swish-swish of the windscreen wipers. Kampung Raja in Besut wasn't sixty miles from Kuala Trengganu, but it seemed a very long way.

We were taken there during school holidays to meet cousins and uncles, aunties and more cousins twice removed, and Toks galore. Toks were older people — grandfather and grandmother, and grand uncles, and anyone else dressed in sarong pelikat, and the Malay baju and the walking stick of senior years. Kampung Raja was dark in the night and long in the the days, but always, always there was a gaggle of people.

My grandfather had a sprawling house in Kampung Raja — village of the ruler — opposite a Malay school. It was as big a house as a child could imagine, with capacity to accommodate a few coachloads of people if the occasion called. But sometimes occasion didn't, and it'd be quieter then, with ladies rustling up things in the back of the house, and my grandfather sitting at his table by the window, poring over some dog-eared kitabs. He kept spotted doves and puffed on cigarettes made from sun-dried leaves filled with strands of tobacco, then rolled into the thin shape of a knitting needle. Kampung Raja was quiet — unsettlingly so — even in the day. There'd be the occasional rumble of a motor car over some distance, or some murmur of conversation from passers by; then the birds, bored by this life of captivity, would lament it so: kur-kur! kur-kur! came their woeful tale. The Malays call them the tekukur.

In the daytime when my cousins were distracted by their own things, I'd walk the ground and stuff myself on jambu or water apple, or star fruit that hung from scrawny trees. Or sometimes I'd walk barefooted across the soft sand in front of the house to the spreading cashew trees — known here as pokok ketereh — by the roadside. The cashews were useless to a growing child, its funny fruit inedible, and its shoots plucked by adults and served at the dining table as an ulam to be eaten with hot sambal or dipped in budu, the dark fish sauce of Trengganu.

At night, when the lampu pam came out, we sat under its bright light to dinner on white sheets spread out across the floor, then the pressure lanterns would hiss the night away, its light fading steadily as time went by. The lampu pam lit many homes and many roadside stalls, with their fabric mantles glowing brightly and miraculously under pressure and kerosene power.

Late into the night when the pressure was dropping and the light turning yellow, we'd gather around Ayah Ngah, my father's brother, and urge him to tell us a story. No, he'd say, he had to go, then he'd relent and tell us a wonderful tale spun out there on the fly, the epic journey of Pak Wé. Pak Wé was an unlikely sarong wearing — batik, of course — baju clad and ketayap topped Trengganu hero, a man who beat the odds and repelled enemies by the power of breaking wind, especially the kentut singgang, Ayah Ngah would say, the force of wind power and Trengganu cookery that turned back many mortals.

When even Pak Wé became tired and the lamp mantle grew even dimmer, Ayah Ngah would rise and pump the lamp again with renewed pressure. Brightness came back to the room, and we knew it was time for sleep and Pak Wé to go.

ß

Growing Up In Trengganu #50976

The ferry was a raft built of blocks of wood that took the weight of four or six vehicles, assorted pedestrians and people cycling into the green yonder. It was pulled by a tug across the Trengganu river in one of its most meancing phases, to the bank across, from where our journey would continue. Ferries crossed many rivers in Trengganu then, in Dungun there was a ferry point, and in Kemaman there was one at a place called Geliga. An express bus once slipped its brakes on the deep incline to the ferry over there and dove into the river. I remember that early evening in Kuala Trengganu when our poor cousin from Seberang Takir came back quite dead and sodden with many other unfortunate souls, all laid out in the back of a lorry.

The road to Besut was heat and dust over a long stretch that wound and dipped through dense jungle. In the monsoon months, seen through the condensation in the window, the view became smudgy watercolour, smearings of green against the brooding sky, and the continual swish-swish-swish of the windscreen wipers. Kampung Raja in Besut wasn't sixty miles from Kuala Trengganu, but it seemed a very long way.

We were taken there during school holidays to meet cousins and uncles, aunties and more cousins twice removed, and Toks galore. Toks were older people — grandfather and grandmother, and grand uncles, and anyone else dressed in sarong pelikat, and the Malay baju and the walking stick of senior years. Kampung Raja was dark in the night and long in the the days, but always, always there was a gaggle of people.

My grandfather had a sprawling house in Kampung Raja — village of the ruler — opposite a Malay school. It was as big a house as a child could imagine, with capacity to accommodate a few coachloads of people if the occasion called. But sometimes occasion didn't, and it'd be quieter then, with ladies rustling up things in the back of the house, and my grandfather sitting at his table by the window, poring over some dog-eared kitabs. He kept spotted doves and puffed on cigarettes made from sun-dried leaves filled with strands of tobacco, then rolled into the thin shape of a knitting needle. Kampung Raja was quiet — unsettlingly so — even in the day. There'd be the occasional rumble of a motor car over some distance, or some murmur of conversation from passers by; then the birds, bored by this life of captivity, would lament it so: kur-kur! kur-kur! came their woeful tale. The Malays call them the tekukur.

In the daytime when my cousins were distracted by their own things, I'd walk the ground and stuff myself on jambu or water apple, or star fruit that hung from scrawny trees. Or sometimes I'd walk barefooted across the soft sand in front of the house to the spreading cashew trees — known here as pokok ketereh — by the roadside. The cashews were useless to a growing child, its funny fruit inedible, and its shoots plucked by adults and served at the dining table as an ulam to be eaten with hot sambal or dipped in budu, the dark fish sauce of Trengganu.

At night, when the lampu pam came out, we sat under its bright light to dinner on white sheets spread out across the floor, then the pressure lanterns would hiss the night away, its light fading steadily as time went by. The lampu pam lit many homes and many roadside stalls, with their fabric mantles glowing brightly and miraculously under pressure and kerosene power.

Late into the night when the pressure was dropping and the light turning yellow, we'd gather around Ayah Ngah, my father's brother, and urge him to tell us a story. No, he'd say, he had to go, then he'd relent and tell us a wonderful tale spun out there on the fly, the epic journey of Pak Wé. Pak Wé was an unlikely sarong wearing — batik, of course — baju clad and ketayap topped Trengganu hero, a man who beat the odds and repelled enemies by the power of breaking wind, especially the kentut singgang, Ayah Ngah would say, the force of wind power and Trengganu cookery that turned back many mortals.

When even Pak Wé became tired and the lamp mantle grew even dimmer, Ayah Ngah would rise and pump the lamp again with renewed pressure. Brightness came back to the room, and we knew it was time for sleep and Pak Wé to go.

ß

Growing Up In Trengganu #50976

Wednesday, October 27, 2004

Breakfasting in Terengganu

My bloggermate Kura-Kura sent in a note today from Kuala Terengganu where he's gone for a short break with his Terengganu family. I hope he will not mind if I post my reply here:

Dear K-K,

Wow, you lucky you. Terengganu during Puasa! That's something I really, really miss, right to the lads who sell the air batu on the jute sacks opposite the kedai Bhiku.

Your description of an everyday scene in a KT extended family is so vivid. I'm this moment trying to recollect my extended family experience in Besut, but my otak's jammed at the moment. We used to go to Besut every school holiday to meet up with the cousins and aunties and uncles and the Toks. There would've been at least 20 people in the house at any one time, and for a child, to see so many people all gadding about in one house was a real marvel, especially as Besut was such a sleepy hollow.

Please eat an akok for me. Is it an akok telor or akok berlauk? Akok telor is the golden boat shaped thingy; sometimes it's made in a large floral shape, in a special Trengganu brass mould probably made near my house in Tanjong. If it's akok berlauk, there's shreds of chicken in it, put in by dainty hands, as only they know.

The names you mentioned in Bukit Besar - places such as Pasir Maghreb - are all alien to me. Is Pasir Maghreb named after Morocco, or after the prayer time when all good men are home with the family? We kids had a term for this time of day, deriving probably from football. The last hit, the last riposte, the last deed, the last prank of the day was called the Buah Maghrib (Buah Ggareb, as we said it), the last big hit of the day before heading for home.

You're right about the sound of the cannon, that's the sound of Trengganu during Ramadhan, and the Genta too. I don't know if the genta is still rung over the hill at iftar and end of sahur. The sounds of the genta in my early days of puasa were struck by a man named Wé, who still lives in Kuala Terengganu. The striker part of the genta was never in place or some madmen would've gone up the hill and rung in the iftar early, or the sahur late. So Wé, whenever he was in charge, had this striking part in his pocket as he clambered up the hill. Once up there, mostly in the dark I should say, he'd fit it back to the bell, and strike it hard when the time was right. He had a little torch about his person I must say, so everything'd be done in good light.

Maybe the genta is silent now because Wé forgot to give the striker thing back to the Powers that Bell in Terengganu. Maybe Wé is still walking the streets of Terengganu in his retirement with the Genta striker in his pocket still, impressing many ladies.

Regards to you and Mrs K-K, and Selamat berbuka!

Glossary:

Air batu = [lit. water block] ice

Akok = Trengganu cake, usu. boat shaped, and golden yellow in colour.

Buah Maghrib/Buah Ggarib = The last kick before Maghrib (Ar.) prayer time.

Genta = Also pron. Geta, a big brass bell on Bukit Puteri, a hill overlooking Kuala Terengganu harbour.

Iftar = [Ar.] Breaking of fast at Maghrib prayer time, sunset.

Kedai = Shop

Otak = brain

Puasa = fast, as in Ramadhan. Fasting month [n.]

Selamat Berbuka = Good wishes for iftar

Tok = Term of respect for old people; specifically, grandfather or grandmother.

Addendum

After posting the above, I received a note from a man who knows more about Terengganu (nay, Trengganu) than I do. He runs a very interesting site called, in Trengganuspeak, Di Bawah Rang Ikang Kering, which is in my handrolled list of blogs in the right hand column. This is what he says:

The mistake was a slip of my typing finger, not K-K's. I am grateful to you, Sir, for having pointed that out.

ß

Breakfasting in Terengganu

Dear K-K,

Wow, you lucky you. Terengganu during Puasa! That's something I really, really miss, right to the lads who sell the air batu on the jute sacks opposite the kedai Bhiku.

Your description of an everyday scene in a KT extended family is so vivid. I'm this moment trying to recollect my extended family experience in Besut, but my otak's jammed at the moment. We used to go to Besut every school holiday to meet up with the cousins and aunties and uncles and the Toks. There would've been at least 20 people in the house at any one time, and for a child, to see so many people all gadding about in one house was a real marvel, especially as Besut was such a sleepy hollow.

Please eat an akok for me. Is it an akok telor or akok berlauk? Akok telor is the golden boat shaped thingy; sometimes it's made in a large floral shape, in a special Trengganu brass mould probably made near my house in Tanjong. If it's akok berlauk, there's shreds of chicken in it, put in by dainty hands, as only they know.

The names you mentioned in Bukit Besar - places such as Pasir Maghreb - are all alien to me. Is Pasir Maghreb named after Morocco, or after the prayer time when all good men are home with the family? We kids had a term for this time of day, deriving probably from football. The last hit, the last riposte, the last deed, the last prank of the day was called the Buah Maghrib (Buah Ggareb, as we said it), the last big hit of the day before heading for home.

You're right about the sound of the cannon, that's the sound of Trengganu during Ramadhan, and the Genta too. I don't know if the genta is still rung over the hill at iftar and end of sahur. The sounds of the genta in my early days of puasa were struck by a man named Wé, who still lives in Kuala Terengganu. The striker part of the genta was never in place or some madmen would've gone up the hill and rung in the iftar early, or the sahur late. So Wé, whenever he was in charge, had this striking part in his pocket as he clambered up the hill. Once up there, mostly in the dark I should say, he'd fit it back to the bell, and strike it hard when the time was right. He had a little torch about his person I must say, so everything'd be done in good light.

Maybe the genta is silent now because Wé forgot to give the striker thing back to the Powers that Bell in Terengganu. Maybe Wé is still walking the streets of Terengganu in his retirement with the Genta striker in his pocket still, impressing many ladies.

Regards to you and Mrs K-K, and Selamat berbuka!

Glossary:

Air batu = [lit. water block] ice

Akok = Trengganu cake, usu. boat shaped, and golden yellow in colour.

Buah Maghrib/Buah Ggarib = The last kick before Maghrib (Ar.) prayer time.

Genta = Also pron. Geta, a big brass bell on Bukit Puteri, a hill overlooking Kuala Terengganu harbour.

Iftar = [Ar.] Breaking of fast at Maghrib prayer time, sunset.

Kedai = Shop

Otak = brain

Puasa = fast, as in Ramadhan. Fasting month [n.]

Selamat Berbuka = Good wishes for iftar

Tok = Term of respect for old people; specifically, grandfather or grandmother.

Addendum

After posting the above, I received a note from a man who knows more about Terengganu (nay, Trengganu) than I do. He runs a very interesting site called, in Trengganuspeak, Di Bawah Rang Ikang Kering, which is in my handrolled list of blogs in the right hand column. This is what he says:

"I think it is not Pasir Magrib but rather Pasar Garib [i.e. The marrket at Maghrib prayer time] along the Pasir Panjang Road. They sell a lot of things like fresh meat. I think they start late, hence the name."

The mistake was a slip of my typing finger, not K-K's. I am grateful to you, Sir, for having pointed that out.

ß

Breakfasting in Terengganu

Sunday, October 24, 2004

Gott Mit Uns

"Now we come at last to the heart of darkness. Now we know, from their own words, that the Bush Regime is a cult — a cult whose god is Power, whose adherents believe that they alone control reality, that indeed they create the world anew with each act of their iron will. And the goal of this will — undergirded by the cult's supreme virtues of war, fury and blind faith — is likewise openly declared: 'Empire.'

You think this is an exaggeration?"

Read More...

ß

Gott Mit Uns

Saturday, October 23, 2004

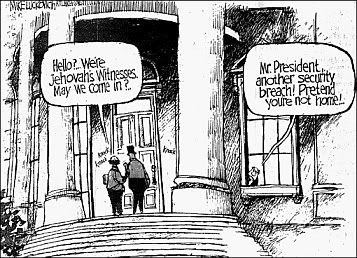

Witness in the Door

Morning's never a good time to discuss the end, but the end-time man was here. He knocked on the door.

"Do you think the world's a troubled place?" he asked, the opening line of Jehovah people.

Unlike most people in the neighbourhood, I never turn away the end-time people. He was a smart man in a neat suit; trim, a strayer from the norm, a lone man with a red Bible. "Do you believe the world is coming to an end?" he tried again, seeing me bleary eyed.

"We Muslims aren't really end-time peddlars, " I said. "When we die it's the end, that's it.The world ends anytime on us that way."

He quoted the Qur'an, chapter 5 or somewhere there, but as I don't care much for people who quote and interpret the Qur'an in English, I let that pass, it was too early in the morning anyway. But as for our Holy Book, it's probably got more end-times than the Bible, I said.

"Why do you think there's trouble," he asked again.

I said I don't know, maybe it's because people are attacking people.

"Why do innocent people die?" he came back.

"You mean why God sends suffering to this world?" I asked.

"Yes," he said. "Why is this heavenly earth so bad?"

"That's to show us it's a better place in the hereafter," I said.

Then he turned on his raw proposition:"Do you believe in sin?" he asked, staring me in the eye.

I would've retorted with something cute, but sensing his serious purpose, I said, "No."

"Do you think my son will take my sins?" I asked.

"No," he replied. "But Jesus died for us."

Then he spoke of the Qur'an, and his red Bible. "My grandmother was a Muslim, but she found turths in the Bible."

"Ah, what a shame, " I replied. "I hope she will come back." It only to made him smile.

"Why are the Muslims having such a bad time as you said?" he came back. I said maybe it's because we're the only people who can stand up to the shenanigans of those folk out there. "If they eradicate us it'll be easier for them to have their way."

"We can fight them just as well," he said, adjusting his trimline tie.

"But there aren't enough of you, there aren't Jehovah's Witness belts sitting on oil in this world," I said.

"What's it about you they don't like?" he asked.

"Well, which group of people are strong enough to resist their devilry and make a hash of what they're after?" I said.

"We too are suffering," he said.

"Yes, I know," I consoled him. "You're banned in Singapore."

And then, turning the drift slightly, I said: "You must come to our Mosque. We have many West Indian brothers."

"I'm not from the West Indies, I'm from Ghana," he said, turning the table.

"Ah, your grandmother. There're Muslims in Ghana..."

"She found love in the Bible," he said, a reminder.

"And I love you for your faith, " I said, "better with than without."

And so he turned away, and gave me a little smile. Maybe for his grandmother.

ß

Witness in the Door

"Do you think the world's a troubled place?" he asked, the opening line of Jehovah people.

Unlike most people in the neighbourhood, I never turn away the end-time people. He was a smart man in a neat suit; trim, a strayer from the norm, a lone man with a red Bible. "Do you believe the world is coming to an end?" he tried again, seeing me bleary eyed.

"We Muslims aren't really end-time peddlars, " I said. "When we die it's the end, that's it.The world ends anytime on us that way."

He quoted the Qur'an, chapter 5 or somewhere there, but as I don't care much for people who quote and interpret the Qur'an in English, I let that pass, it was too early in the morning anyway. But as for our Holy Book, it's probably got more end-times than the Bible, I said.

"Why do you think there's trouble," he asked again.

I said I don't know, maybe it's because people are attacking people.

"Why do innocent people die?" he came back.

"You mean why God sends suffering to this world?" I asked.

"Yes," he said. "Why is this heavenly earth so bad?"

"That's to show us it's a better place in the hereafter," I said.

Then he turned on his raw proposition:"Do you believe in sin?" he asked, staring me in the eye.

I would've retorted with something cute, but sensing his serious purpose, I said, "No."

"Do you think my son will take my sins?" I asked.

"No," he replied. "But Jesus died for us."

Then he spoke of the Qur'an, and his red Bible. "My grandmother was a Muslim, but she found turths in the Bible."

"Ah, what a shame, " I replied. "I hope she will come back." It only to made him smile.

"Why are the Muslims having such a bad time as you said?" he came back. I said maybe it's because we're the only people who can stand up to the shenanigans of those folk out there. "If they eradicate us it'll be easier for them to have their way."

"We can fight them just as well," he said, adjusting his trimline tie.

"But there aren't enough of you, there aren't Jehovah's Witness belts sitting on oil in this world," I said.

"What's it about you they don't like?" he asked.

"Well, which group of people are strong enough to resist their devilry and make a hash of what they're after?" I said.

"We too are suffering," he said.

"Yes, I know," I consoled him. "You're banned in Singapore."

And then, turning the drift slightly, I said: "You must come to our Mosque. We have many West Indian brothers."

"I'm not from the West Indies, I'm from Ghana," he said, turning the table.

"Ah, your grandmother. There're Muslims in Ghana..."

"She found love in the Bible," he said, a reminder.

"And I love you for your faith, " I said, "better with than without."

And so he turned away, and gave me a little smile. Maybe for his grandmother.

ß

Witness in the Door

Thursday, October 21, 2004

Heart of Darkness

Suddenly the world is beseiged by evil, and then the battle against it. Unbeknown to the masses, both the evil and the presumed 'good' that are against it are fictions, they can only be so. Nothing can be so simply black and white, yet it is looking so now: the war against terrorism, either you're with us or you're against us. The world is in a terrible fix, but who's behind it all?

We see shadows on the wall, of wolves and men and beasts, trundling around, calling orders. Sometimes they're known as the Neocons, sometimes they're turbaned with beards, with a wild look in their eyes. But what manner of beast are they? And is Islam really the demon they're looking to exorcise or is it demonisation for a purpose?

Last night the BBC showed the first of its three part documentary on the Power of Nightmares about the growth of this East-West hysteria. It is steeped in religious extremism on both sides, the ultra-conservative religious fundamentalists in America and the Islamists in the East, led, allegedly, by Syed Qutb, a controversial thinker who was tortured and finally hanged by the regime of Gamel Abdel Nasser.

What is interesting in this series is its thesis of the creation of fear as a ruling ideology to rein in the masses. It raises many questions, but perhaps it doesn't raise enough that ought to be examined more. Who, for instance, is Bin Laden? Who Musab Al-Zarkawi? Who's really now behind the terrorist kidnappers in Iraq who're terrorising and beheading people mercilessly, brutally, in the name of what?

We do not know the answers, but the end result for now is that Islam is tarnished and demonised. It is as if there're people out there ever ready to make a public image of themselves brandishing knives, posing beneath balaclavas in cocky stances, while the poor, wretched prisoner kneels before them, gagged and bound, pleading for mercy. And the obligatory cry that chills the blood when the deed is done, Allahu Akbar!. And this is a deed done with a large banner bearing the Shuhada in the backdrop. The average Muslim in the street cringe when they see that, but these people are allegedly fanatically devoted to Islam. What powerful image for the bashers of Islam, what powerful symbols stuck in the heads of ordinary people out there.

There are the Pearls and Wolfowitzes and all those other denizens of this clash of civlisations secnario who are telling us know that they've told us so. What Bruce Bartlett, former doemstic policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and Treasury official to Bush senior said of Bush and his battle against al-Qaeda the other day was so stark it's worth repeating here: ''George W. Bush is so clear-eyed about Al Qaeda and the Islamic fundamentalist enemy. He believes you have to kill them all. They can't be persuaded, that they're extremists, driven by a dark vision. He understands them, because he's just like them."

There are powerful people out there now, and largely they're inspired by Leo Strauss, spiritual leader of this new band of neocon evil bashers. Strauss studied in Germany under Husserl and Heidegger and then went on to the States to continue his teaching career. He had strong views about the need to fight against evil as he saw it, but mostly he believed that the elite should use deception, religious fervour and perpetual war to control the ignorant masses.

§Leo Strauss' Philosophy of Deception §Leo Strauss and the Straussians §The long reach of Leo Strauss

ß

Heart of Darkness

We see shadows on the wall, of wolves and men and beasts, trundling around, calling orders. Sometimes they're known as the Neocons, sometimes they're turbaned with beards, with a wild look in their eyes. But what manner of beast are they? And is Islam really the demon they're looking to exorcise or is it demonisation for a purpose?

Last night the BBC showed the first of its three part documentary on the Power of Nightmares about the growth of this East-West hysteria. It is steeped in religious extremism on both sides, the ultra-conservative religious fundamentalists in America and the Islamists in the East, led, allegedly, by Syed Qutb, a controversial thinker who was tortured and finally hanged by the regime of Gamel Abdel Nasser.

What is interesting in this series is its thesis of the creation of fear as a ruling ideology to rein in the masses. It raises many questions, but perhaps it doesn't raise enough that ought to be examined more. Who, for instance, is Bin Laden? Who Musab Al-Zarkawi? Who's really now behind the terrorist kidnappers in Iraq who're terrorising and beheading people mercilessly, brutally, in the name of what?

We do not know the answers, but the end result for now is that Islam is tarnished and demonised. It is as if there're people out there ever ready to make a public image of themselves brandishing knives, posing beneath balaclavas in cocky stances, while the poor, wretched prisoner kneels before them, gagged and bound, pleading for mercy. And the obligatory cry that chills the blood when the deed is done, Allahu Akbar!. And this is a deed done with a large banner bearing the Shuhada in the backdrop. The average Muslim in the street cringe when they see that, but these people are allegedly fanatically devoted to Islam. What powerful image for the bashers of Islam, what powerful symbols stuck in the heads of ordinary people out there.

There are the Pearls and Wolfowitzes and all those other denizens of this clash of civlisations secnario who are telling us know that they've told us so. What Bruce Bartlett, former doemstic policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and Treasury official to Bush senior said of Bush and his battle against al-Qaeda the other day was so stark it's worth repeating here: ''George W. Bush is so clear-eyed about Al Qaeda and the Islamic fundamentalist enemy. He believes you have to kill them all. They can't be persuaded, that they're extremists, driven by a dark vision. He understands them, because he's just like them."

There are powerful people out there now, and largely they're inspired by Leo Strauss, spiritual leader of this new band of neocon evil bashers. Strauss studied in Germany under Husserl and Heidegger and then went on to the States to continue his teaching career. He had strong views about the need to fight against evil as he saw it, but mostly he believed that the elite should use deception, religious fervour and perpetual war to control the ignorant masses.

§Leo Strauss' Philosophy of Deception §Leo Strauss and the Straussians §The long reach of Leo Strauss

ß

Heart of Darkness

Wednesday, October 20, 2004

Growing Up in Trengganu #39506

If the sound of burping was to be expected at lunch-time during Ramadhan in Kuala Trengganu, it would've come from those cubicles behind the drapes in the rambunctious cafe next door to the Panggung Mat Min. The Panggung was one of our two local cinemas, officially called the Sultana, a shortlived name soon overtaken by the fame of its own doorkeeper, a man named Mat Min, whose name — in the mouths of the public — soon became the cinema proper.

The sleazy cafe by the Panggung Mak Ming (as we called him in Trengganuspeak) had a frontage on the main road on the edge of our Chinatown. It differed from your common and garden coffee shop by dint of the pelayan ladies who ran hither and thither from table to table with coffee as black as sin and sin maybe, for afters. The word pelayan itself is relatively harmless if you look it up in a Malay dictionary, but in Trengganuspeak then, words were never what they seemed to be, and the pelayan was not just your lady server, just as a bujang woman wasn't your dainty spinster. If an orang bujang were to cross your path you'd quickly avert your eyes if you were mosque going people.

It differed from your common and garden coffee shop by dint of the pelayan ladies who ran hither and thither from table to table with coffee as black as sin and sin maybe, for afters. The word pelayan itself is relatively harmless if you look it up in a Malay dictionary, but in Trengganuspeak then, words were never what they seemed to be, and the pelayan was not just your lady server, just as a bujang woman wasn't your dainty spinster. If an orang bujang were to cross your path you'd quickly avert your eyes if you were mosque going people.

Ramadhan was of course a month of abstinence, but not behind those cafe covers. There were straight-backed chairs in the cafe sleaze, facing one another; with backs so tall that two chairs tête-á-tête, lined against the wall, formed a neat cubicle with the eating table in between and the entrance and exit in the broad gangway in the cafe centre. They were lined on opposite walls, as I remember, with the centre area of the cafe filled with round, marble topped tables, taken up by punters who felt no reason to be lying low. I imagine the cafe owner, on the eve of Ramadhan, scurrying to the dusty storeroom for the drapes to hang across the entrance to his Ramadhan tête-á-tête cubicles.

This sleaze cafe came back to me when I was watching an early instalment of Star Wars, when Hans Solo and friends ventured into the cafe at the edge of the universe, filled with shady types and blubbery people. Sleaze cafe by the Panggong Mat Min was a place like that: I don't think I saw anyone in there that I recognised or knew, they were people that sprang out of a Trengganu that I didn't know, with proclivities to make you gawp away the time of day. In Ramadhan they ate behind the drapes, in other months they sowed wild oats in this lively corner.

The Panggong Mat Min wasn't a favourite, but sometimes we'd hang there to look at the cinema posters. They showed Cathay Kris only over there, because Shaw Brothers productions were the privilege of the Capitol next door. One day, while ogling at the shapeliness of Rose Yatimah, maybe, we heard a loud shriek from the woman at cafe sleaze, then saw a man wearing a smirk for a face, hurrying away from her. "Cekor ***** dapat pitis samah!" she said, mocking a short chase that ended in a smile. It was quite a daring thing to say in the open air of Kuala Trengganu, but the pelayan were that kind of people.

Cekor was then — as now — an act of daring, the grabbing of something succulent, like meat, and pitis samah was worth fifty cents in those Trengganu days. I shall spare you the asterisks, dear reader, but I went home that day with my little head thinking of the wonders of nature.

ß

Growing Up in Trengganu #39506

The sleazy cafe by the Panggung Mak Ming (as we called him in Trengganuspeak) had a frontage on the main road on the edge of our Chinatown.

It differed from your common and garden coffee shop by dint of the pelayan ladies who ran hither and thither from table to table with coffee as black as sin and sin maybe, for afters. The word pelayan itself is relatively harmless if you look it up in a Malay dictionary, but in Trengganuspeak then, words were never what they seemed to be, and the pelayan was not just your lady server, just as a bujang woman wasn't your dainty spinster. If an orang bujang were to cross your path you'd quickly avert your eyes if you were mosque going people.

It differed from your common and garden coffee shop by dint of the pelayan ladies who ran hither and thither from table to table with coffee as black as sin and sin maybe, for afters. The word pelayan itself is relatively harmless if you look it up in a Malay dictionary, but in Trengganuspeak then, words were never what they seemed to be, and the pelayan was not just your lady server, just as a bujang woman wasn't your dainty spinster. If an orang bujang were to cross your path you'd quickly avert your eyes if you were mosque going people.

Ramadhan was of course a month of abstinence, but not behind those cafe covers. There were straight-backed chairs in the cafe sleaze, facing one another; with backs so tall that two chairs tête-á-tête, lined against the wall, formed a neat cubicle with the eating table in between and the entrance and exit in the broad gangway in the cafe centre. They were lined on opposite walls, as I remember, with the centre area of the cafe filled with round, marble topped tables, taken up by punters who felt no reason to be lying low. I imagine the cafe owner, on the eve of Ramadhan, scurrying to the dusty storeroom for the drapes to hang across the entrance to his Ramadhan tête-á-tête cubicles.

This sleaze cafe came back to me when I was watching an early instalment of Star Wars, when Hans Solo and friends ventured into the cafe at the edge of the universe, filled with shady types and blubbery people. Sleaze cafe by the Panggong Mat Min was a place like that: I don't think I saw anyone in there that I recognised or knew, they were people that sprang out of a Trengganu that I didn't know, with proclivities to make you gawp away the time of day. In Ramadhan they ate behind the drapes, in other months they sowed wild oats in this lively corner.

The Panggong Mat Min wasn't a favourite, but sometimes we'd hang there to look at the cinema posters. They showed Cathay Kris only over there, because Shaw Brothers productions were the privilege of the Capitol next door. One day, while ogling at the shapeliness of Rose Yatimah, maybe, we heard a loud shriek from the woman at cafe sleaze, then saw a man wearing a smirk for a face, hurrying away from her. "Cekor ***** dapat pitis samah!" she said, mocking a short chase that ended in a smile. It was quite a daring thing to say in the open air of Kuala Trengganu, but the pelayan were that kind of people.

Cekor was then — as now — an act of daring, the grabbing of something succulent, like meat, and pitis samah was worth fifty cents in those Trengganu days. I shall spare you the asterisks, dear reader, but I went home that day with my little head thinking of the wonders of nature.

ß

Growing Up in Trengganu #39506

Tuesday, October 19, 2004

Basic Instincts

Bush hears voices, that much we know. No, not just from the mike he's wired up with whenever he's meeting the press or debating issues, but also from God, telling him to do this and that. As the world already knows, the Neocons are fundamentalists on a mission. And they're fired in this by the zeal of Christian Zionists who're awaiting the Rapture. These are Zionists who hope, one day, to convert Jews to Christianity.

So there are rumblings among some Republicans about the suitability of Bush for President now. Brent Scowcroft has said it, now it's the turn of Bruce Bartlett. Bartlett was domestic policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and Treasury official to Bush the elder. His expression of concern centred around Bush junior's instincts and Messianic "God-told-me-so" vision.

The battle against al-Qaeda isn't just a battle against terrorism; it's a mission in black and white, good against evil. According to Ron Suskind of the New York Times, Bartlett said this of Bush:''This is why George W. Bush is so clear-eyed about Al Qaeda and the Islamic fundamentalist enemy. He believes you have to kill them all. They can't be persuaded, that they're extremists, driven by a dark vision. He understands them, because he's just like them."

The plans for war to take Iraq were laid down a year before 9-11 happened, as part of the President's global plans soon after he took office. So all those talk about WMDs and Saddam's links to al-Qaeda were just fabrications — or poor intelligence — as now acknowledged, to start the attack. Even Blair has admitted so now, but has still refused to apologise because in the end, the toppling of Saddam Hussain was worth it, just as Madeline Albright once said that having all those children dead in Iraq was worth it.

Democrat senator Joseph Biden of Delaware once asked Bush about his war on Iraq, about all those forces he was unleashing — sunnis, shiites, disbanding Saddam's army, securing the oilfields — how could you be so sure if you didn't know the facts?

"My instincts, " Bush replied. "My instincts."

Funny, isn't it, when they talk about Iraq, they seldom talk about the suffering of the people

ß

Basic Instincts

So there are rumblings among some Republicans about the suitability of Bush for President now. Brent Scowcroft has said it, now it's the turn of Bruce Bartlett. Bartlett was domestic policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and Treasury official to Bush the elder. His expression of concern centred around Bush junior's instincts and Messianic "God-told-me-so" vision.

The battle against al-Qaeda isn't just a battle against terrorism; it's a mission in black and white, good against evil. According to Ron Suskind of the New York Times, Bartlett said this of Bush:''This is why George W. Bush is so clear-eyed about Al Qaeda and the Islamic fundamentalist enemy. He believes you have to kill them all. They can't be persuaded, that they're extremists, driven by a dark vision. He understands them, because he's just like them."

The plans for war to take Iraq were laid down a year before 9-11 happened, as part of the President's global plans soon after he took office. So all those talk about WMDs and Saddam's links to al-Qaeda were just fabrications — or poor intelligence — as now acknowledged, to start the attack. Even Blair has admitted so now, but has still refused to apologise because in the end, the toppling of Saddam Hussain was worth it, just as Madeline Albright once said that having all those children dead in Iraq was worth it.

Democrat senator Joseph Biden of Delaware once asked Bush about his war on Iraq, about all those forces he was unleashing — sunnis, shiites, disbanding Saddam's army, securing the oilfields — how could you be so sure if you didn't know the facts?

"My instincts, " Bush replied. "My instincts."

Funny, isn't it, when they talk about Iraq, they seldom talk about the suffering of the people

ß

Basic Instincts

Monday, October 18, 2004

Dinner With Condi

Brent Scowcroft was at dinner with Condoleeza Rice, munching on foreign policy and chewing the cud, when news came of Ariel Sharon wanting out of Gaza.

"Ah," said Condi, ever the optimist, "at least that's good news!"

"That's bad news," differed Scowcroft. And what's bad about that is that Sharon will just say I'm done with this, get the Wall going, and I'm going home.

Scowcroft, former National Security adviser to Bush senior, also said, though not over dinner with Condi, but in the Financial Times on October 13, that President George Dubya Bush is under the spell of Ariel Sharon.

Now, who could've known that?

ß

Dinner With Condi

"Ah," said Condi, ever the optimist, "at least that's good news!"

"That's bad news," differed Scowcroft. And what's bad about that is that Sharon will just say I'm done with this, get the Wall going, and I'm going home.

Scowcroft, former National Security adviser to Bush senior, also said, though not over dinner with Condi, but in the Financial Times on October 13, that President George Dubya Bush is under the spell of Ariel Sharon.

"Sharon just has him wrapped around his little finger, I think the president is mesmerised. When there is a suicide attack [followed by a reprisal] Sharon calls the president and says, 'I'm on the front line of terrorism', and the president says, 'Yes, you are. . . ' He [Mr Sharon] has been nothing but trouble," Scowcroft said.

Now, who could've known that?

ß

Dinner With Condi

Order By Chaos

A friend from Somalia told me that his country's at a standstill. There's peace of sorts, he said, with the warlords holding sway. Where do the warlords get their ackers? Well, that's the million dollar question, and a formula for holding a potential enemy at bay. Feed the warlords, keep Somalia divided, and pin it down there for now. But who goes there?

Somalia could be one strong, happy country, he said, but it is now sadly divided by the forces that have the money and firepower.

he said, but it is now sadly divided by the forces that have the money and firepower.

Not long ago Somalia was the bloodied nose of America. Now it's just a forgotten mangled backyard, with wrecks of battle, happy warlords and happier people who put them there in the first place to obstruct progress towards any meaningful way.

In Londra the Somalis are gathering as large urban tribes, seemingly prosperous, with plenty of purchasing power to buy vacant shophouses in derelict corners of the East, West and northwest. They are a conspicuous community of bus drivers, shopkeepers, and, surprisingly, cybercafe owners. They are a tuned in, plugged on, stoned out people. This last thing's worrying my friend more than just a bit, because, of all the forbidden drugs on the list, the Somali qat isn't on the list at all.

There're qat leaves aplenty in the Somali market; each week, in my area, boxes of qat leaves arrive at the Somali qat centres, my friend observed.

Why so? I asked. Well, my Somali friend said with a smile, this is to hold them in check, in their fantasy qat-chewing world. My friend, ever the cynic.

But then, he said, looking back home at Somalia; don't take these forces of turmoil too lightly. In Sudan the Janjaweeds — literally Djinns on horseback — aren't just Arabs as they say, they're people from Chad and nearby areas as well, there're Arabs riding against the government in North Darfur and Arabs riding for the government in the South; and there're black Sudanese people armed by someone to wreak revenge against all the others. In Darfur both Arabs and non-Arabs are against the central government because of neglect, and the Arabs have been in the Sultanate of Darfur for some 600 years, descendants of a tribe from Iraq that took the emigration route during the Fatimids. So my friend said.

From Somalia to Sudan, then to America.

Warlord armies are on the rise, my friend said, that's something that's gone unnoticed. In September Paul Wolfowitz was speaking up for Bush in Congress for a US$500 million seed money to arm and train local militias in troubled areas of the world that are said to be potential enemies or "harbouring terrorists". So stand back now for rabid fundamentalists, bareback riders, warlord adventurers, drug cartel operators or just your local petty thug, all armed to the teeth, all taking up a cause.

Now, where have we seen all that before?

ß

Order By Chaos

Somalia could be one strong, happy country,

he said, but it is now sadly divided by the forces that have the money and firepower.

he said, but it is now sadly divided by the forces that have the money and firepower.

Not long ago Somalia was the bloodied nose of America. Now it's just a forgotten mangled backyard, with wrecks of battle, happy warlords and happier people who put them there in the first place to obstruct progress towards any meaningful way.

In Londra the Somalis are gathering as large urban tribes, seemingly prosperous, with plenty of purchasing power to buy vacant shophouses in derelict corners of the East, West and northwest. They are a conspicuous community of bus drivers, shopkeepers, and, surprisingly, cybercafe owners. They are a tuned in, plugged on, stoned out people. This last thing's worrying my friend more than just a bit, because, of all the forbidden drugs on the list, the Somali qat isn't on the list at all.

There're qat leaves aplenty in the Somali market; each week, in my area, boxes of qat leaves arrive at the Somali qat centres, my friend observed.

Why so? I asked. Well, my Somali friend said with a smile, this is to hold them in check, in their fantasy qat-chewing world. My friend, ever the cynic.

But then, he said, looking back home at Somalia; don't take these forces of turmoil too lightly. In Sudan the Janjaweeds — literally Djinns on horseback — aren't just Arabs as they say, they're people from Chad and nearby areas as well, there're Arabs riding against the government in North Darfur and Arabs riding for the government in the South; and there're black Sudanese people armed by someone to wreak revenge against all the others. In Darfur both Arabs and non-Arabs are against the central government because of neglect, and the Arabs have been in the Sultanate of Darfur for some 600 years, descendants of a tribe from Iraq that took the emigration route during the Fatimids. So my friend said.

From Somalia to Sudan, then to America.

Warlord armies are on the rise, my friend said, that's something that's gone unnoticed. In September Paul Wolfowitz was speaking up for Bush in Congress for a US$500 million seed money to arm and train local militias in troubled areas of the world that are said to be potential enemies or "harbouring terrorists". So stand back now for rabid fundamentalists, bareback riders, warlord adventurers, drug cartel operators or just your local petty thug, all armed to the teeth, all taking up a cause.

Now, where have we seen all that before?

ß

Order By Chaos

Thursday, October 14, 2004

Growing Up In Trengganu #39472

The ice blocks came a-rasping especially in those parched days when Ramadhan came to visit us. In the Trengganu of those days the fridge wasn't a commonplace of the home, so we stood in the wide space in front of Bhiku's coffee shop as the ice blocks arrived when the shadows were lengthening and the day was coming to a close.

They came wrapped in sawdust and the gunny — guni — sacks made of jute, brought to us, maybe six to eight blocks to a carrier, by a special mode of transport. These were the basikal kaki tiga, pedalled by men, whose three-wheeled transporter worked on the same principle as the rickshaw with the pedaller behind the passenger seat. But on its front the basikal kaki tiga had an open box placed on a low chassis, with the leading side left open, and a metal bar placed on the box edge in front of the pedaller for him to rest his arms as he pedalled, and to turn the vehicle left and right as he journeyed along.

The basikal kaki tiga men were a macho breed with an independent mien, yet to a man they followed an unofficial dress code. They had a batik sarong wrapped around their waist, with the hem raised above the knees; and underneath this flowery delight they wore a pair of khaki shorts. They would be shirtless mostly, or maybe they'd wear a T-shirt top, and then, by dint of some arcane rule, they had a sarong cape draped over their backs, with the two upper corners tied in a knot under their chin. These were batik sarongs of loud patterns, of leaves and flowers and Trengganu made, and there was nothing sissy about that except in the minds of the orang luar of the other coast. When we moved to Kuala Lumpur, much later, my father sometimes slipped out of the house, to the clothesline maybe, wearing the Trengganu batik, and somewhere in our family album there's probably a photograph of him still, doing just that.

But meantime, in front of the Bhiku shop there was already some loud rasping of the saw's teeth, and a sharp thwack! as the ice was sawn and broken into smaller blocks. This is, to me, the sound of Ramadhan in Kuala Trengganu, of an afternoon in the fasting month when crowds began to mill in front of the Bhiku shop for cakes, for rice and sugar to stock up with, and for the mini block or a half of that soothing ice, taken away in a page from some old newspaper, to take home and fracture again into glittery bits that bobbed and floated in a jugful of sweet, milky sirap.

This trade in ice blocks was the business of bigger boys, and the pedal transporter men with their bilhooks for hands. My father told me that those ice blocks came from a factory in Pulau Kambing — Goat's Island — which wasn't an island at all but a semi-industrial linear township on the bank of the Trengganu. A funny place for goats to be, for water to freeze to ice. The little entrepreneurs made their 'fortune' in Ramadhan from those smaller blocks that they bought and resold for a little profit. All you needed was a guni sack and a place in front of the Bhiku shop to lay it out. And then, at the first sound of the rasping and the thwacking of the ice, you rush to grab a block or three to resell on your mat for a small profit.

It was a profitable venture which begot more noise. Profits from the ice trade were used to buy a thing called carbide which, when placed in water in a bamboo cannon and lit, produced a boom that made the old melatah. Melatah is a Malay-Eskimo hysteria triggered by sudden shocks or noise. I know little about the Inuits, but among the Malays, the afflicted seem to be mostly women of a certain age. So boom! went the bamboo cannon, back came a diarrhoea of words from some senior women, taken from their store of unspoken expletives.

Puasa in our household, as in other households, was serious business. My mother would produce a special mould of brass that she'd been keeping in store since Ramadhan last, fill its boat shaped holes with a liquid concoction of flour and sugar and eggs and stuff, and cover them all up with the flat brass lid that's hinged to the top. On the top surface of this lid she'd burn coconut husks dried in the sun for months ahead, and underneath the apparatus she'd light a fire from wood; and the miracle it produced was called akok. Akoks were succulent morsels of golden dreams, moist in the hand and deliciously sweet, with the cloying taste of some distant past, lilting and dancing daintily on tickled taste buds.

There were other delights too in Ramadhan, of course. There was the nekbat, a little something drenched in syrup, and there was my favourite, the hasidah which was stirred and stirred in a cauldron of brass until the ingredients became a sticky, greasy goo of exquisite stuff. The hasidah paste is then placed on a tray or a plate, flattened to a smooth surface, then, using a special pair of tongs with saw-edge teeth, patterns are pinched out on it in ridges and dips. In the dips would be poured crisp flakes of shallots, freshly fried.

Recently we heard the sad news that our cousin Mat Tepek had died. Mat — God rest his soul — was even smaller than us when he had his encounter with the hasidah, which he started to tepek — stick — to the wall of our house. So Tepek he became, and Tepek he died.

ß

Growing Up In Trengganu #39472

They came wrapped in sawdust and the gunny — guni — sacks made of jute, brought to us, maybe six to eight blocks to a carrier, by a special mode of transport. These were the basikal kaki tiga, pedalled by men, whose three-wheeled transporter worked on the same principle as the rickshaw with the pedaller behind the passenger seat. But on its front the basikal kaki tiga had an open box placed on a low chassis, with the leading side left open, and a metal bar placed on the box edge in front of the pedaller for him to rest his arms as he pedalled, and to turn the vehicle left and right as he journeyed along.

The basikal kaki tiga men were a macho breed with an independent mien, yet to a man they followed an unofficial dress code. They had a batik sarong wrapped around their waist, with the hem raised above the knees; and underneath this flowery delight they wore a pair of khaki shorts. They would be shirtless mostly, or maybe they'd wear a T-shirt top, and then, by dint of some arcane rule, they had a sarong cape draped over their backs, with the two upper corners tied in a knot under their chin. These were batik sarongs of loud patterns, of leaves and flowers and Trengganu made, and there was nothing sissy about that except in the minds of the orang luar of the other coast. When we moved to Kuala Lumpur, much later, my father sometimes slipped out of the house, to the clothesline maybe, wearing the Trengganu batik, and somewhere in our family album there's probably a photograph of him still, doing just that.

But meantime, in front of the Bhiku shop there was already some loud rasping of the saw's teeth, and a sharp thwack! as the ice was sawn and broken into smaller blocks. This is, to me, the sound of Ramadhan in Kuala Trengganu, of an afternoon in the fasting month when crowds began to mill in front of the Bhiku shop for cakes, for rice and sugar to stock up with, and for the mini block or a half of that soothing ice, taken away in a page from some old newspaper, to take home and fracture again into glittery bits that bobbed and floated in a jugful of sweet, milky sirap.

This trade in ice blocks was the business of bigger boys, and the pedal transporter men with their bilhooks for hands. My father told me that those ice blocks came from a factory in Pulau Kambing — Goat's Island — which wasn't an island at all but a semi-industrial linear township on the bank of the Trengganu. A funny place for goats to be, for water to freeze to ice. The little entrepreneurs made their 'fortune' in Ramadhan from those smaller blocks that they bought and resold for a little profit. All you needed was a guni sack and a place in front of the Bhiku shop to lay it out. And then, at the first sound of the rasping and the thwacking of the ice, you rush to grab a block or three to resell on your mat for a small profit.

It was a profitable venture which begot more noise. Profits from the ice trade were used to buy a thing called carbide which, when placed in water in a bamboo cannon and lit, produced a boom that made the old melatah. Melatah is a Malay-Eskimo hysteria triggered by sudden shocks or noise. I know little about the Inuits, but among the Malays, the afflicted seem to be mostly women of a certain age. So boom! went the bamboo cannon, back came a diarrhoea of words from some senior women, taken from their store of unspoken expletives.

Puasa in our household, as in other households, was serious business. My mother would produce a special mould of brass that she'd been keeping in store since Ramadhan last, fill its boat shaped holes with a liquid concoction of flour and sugar and eggs and stuff, and cover them all up with the flat brass lid that's hinged to the top. On the top surface of this lid she'd burn coconut husks dried in the sun for months ahead, and underneath the apparatus she'd light a fire from wood; and the miracle it produced was called akok. Akoks were succulent morsels of golden dreams, moist in the hand and deliciously sweet, with the cloying taste of some distant past, lilting and dancing daintily on tickled taste buds.

There were other delights too in Ramadhan, of course. There was the nekbat, a little something drenched in syrup, and there was my favourite, the hasidah which was stirred and stirred in a cauldron of brass until the ingredients became a sticky, greasy goo of exquisite stuff. The hasidah paste is then placed on a tray or a plate, flattened to a smooth surface, then, using a special pair of tongs with saw-edge teeth, patterns are pinched out on it in ridges and dips. In the dips would be poured crisp flakes of shallots, freshly fried.

Recently we heard the sad news that our cousin Mat Tepek had died. Mat — God rest his soul — was even smaller than us when he had his encounter with the hasidah, which he started to tepek — stick — to the wall of our house. So Tepek he became, and Tepek he died.

ß

Growing Up In Trengganu #39472

Wednesday, October 13, 2004

The Thing of Shapes to Come

"The US government move to shut down nearly two dozen antiwar, anti-globalization web sites on October 7 is an unprecedented exercise of police power against political dissent on the Internet.

"The shutdown was carried out by Rackspace, a US-based web-hosting company with offices in San Antonio, Texas, and greater London, in response to an order from the FBI requiring it to turn over two of its British servers that were hosting dozens of Indymedia sites. There are conflicting accounts of the legal process, with Indymedia attributing the order to a US federal district court, while the Electronic Freedom Foundation, which is supplying legal representation to the group, describes it as a 'commissioner's order' directly from the FBI itself."

Read More...

ß

The Thing of Shapes to Come

The Arab and the Camel

On Edward Said, I said that part of the strategy of his detractors was to rubbish everything he said. Said wasn't qualified to write about the Orient and its study because he wasn't, well, an orientalist. This is against the spirit of learning that I know, and besides, woe betide the day when, to write about holes you have to be yourself in it, or have to have spent your life looking at it. The man who's just appeared on the hilltop may have a better perspective of it than you know about.